What’s the purpose of the Midcourse Report?

The Physical Activity Guidelines emphasizes why people need to engage in physical activity and what dose of physical activity they need to get health benefits. The Midcourse Report focuses on how and where to do physical activity and reinforces the amounts and types of physical activity older Americans need. The report highlights strategies to support physical activity among older adults age 65 years and older in a variety of settings — so they can get the benefits of physical activity outlined in the Guidelines.

Who can use the Midcourse Report?

The primary audiences for the Midcourse Report are:

- Policymakers

- Exercise and health professionals

- Health care providers

- Gerontologists

- Built environment professionals

- Local, state, territorial, and tribal leaders

- Others working with older adults

But everyone has a role to play in increasing physical activity levels among older adults and encouraging progress toward meeting the Guidelines. Family members, friends, caregivers, organizations, communities, and many others across different sectors can contribute to these efforts.

Why does the Midcourse Report focus on older adults?

Older adults were selected for this report because they’re a growing population with low rates of physical activity and because of the physical, mental, social, and economic benefits of physical activity for older adults.

Currently, less than 15 percent of older adults age 65 years and older meet the aerobic and muscle-strengthening physical activity recommendations in the Guidelines. And adults in the United States become less active as they age: According to the 2018 National Health Interview Survey, only 7 percent of adults age 80 years and older met the recommendations in the Guidelines (both aerobic and muscle-strengthening components) during leisure-time physical activity, compared to 17 percent of adults ages 65 to 69 years.

Regular physical activity can help prevent or manage many costly chronic conditions that are common in older adults, including heart disease and stroke, cancer, diabetes, obesity, and arthritis. Regular physical activity can also help older adults:

- Protect against osteoporosis (bone disease) and age-related sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass and strength)

- Lower their risk of falls — and make it less likely they’ll get hurt if they do fall

On top of the many health benefits, physical activity can offer older adults a chance to spend time with friends and family, enjoy the outdoors, feel more energetic, and live independently for longer.

What works to get older adults moving?

This Midcourse Report highlights a variety of strategies that can be implemented wherever older adults spend their time, including in community, health care, and home settings. These strategies include:

- Policy, systems, and environmental approaches

- Behavior change

- Physical activity programs

Policy, systems, and environmental approaches — like those related to transportation and neighborhood environments — aim to create safe, easy access to physical activity opportunities. For example, 1 strategy to successfully increase physical activity among older adults is to make communities more walkable through community design.

Behavior change strategies seek to influence knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs related to physical activity. Behavior change approaches, like physical activity counseling, are often part of physical activity programs and interventions and can help increase self-efficacy and encourage people to get active.

Physical activity programs can help older adults find ways to be active that fit their everyday lives. Structured exercise programs guide people through specific exercises, while lifestyle-based physical activity programs encourage people to get more active throughout the day — either through structured exercise or daily activities, like chores or walking to the store.

Does the Midcourse Report change the key guidelines for physical activity for older adults?

The key guidelines for older adults have not changed. The Midcourse Report focuses on implementation strategies to increase physical activity among older adults and help them meet the Guidelines.

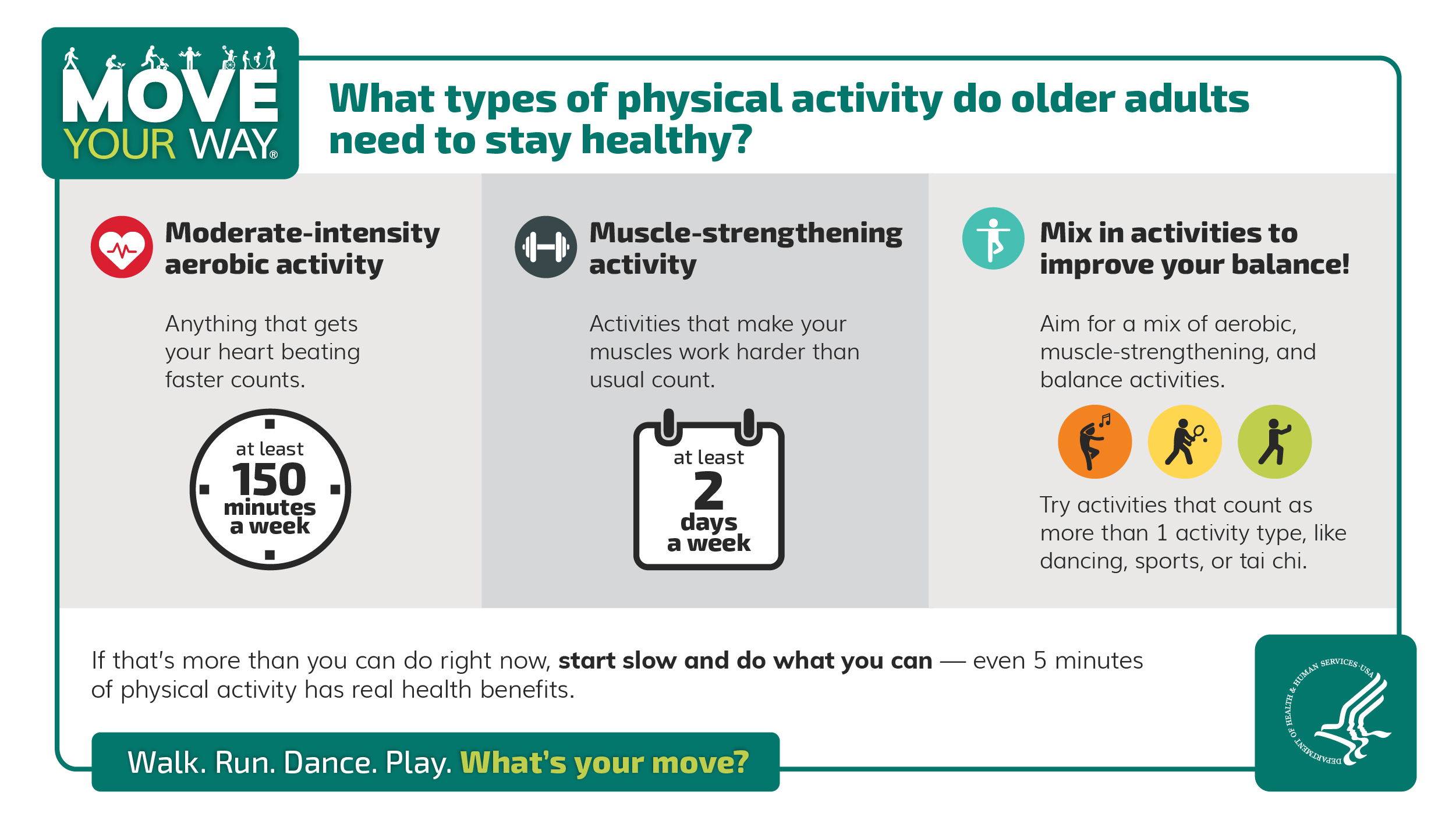

The graphic below outlines the amount and types of activity the Guidelines recommends for older adults:

How was the Midcourse Report developed?

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) contracted a literature review team to work with federal staff to review the evidence on effective strategies for increasing physical activity among older adults — and to summarize their findings in a report, the Physical Activity and Older Adults Systematic Literature Review. This work was supported by the 2022 President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition Science Board, which consisted of 11 experts in the fields of physical activity and aging. The literature review examined how effective a variety of settings are at increasing physical activity among older adults.

HHS based the Midcourse Report primarily on this literature review — and successful interventions from Step It Up! The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Walking and Walkable Communities and The Guide to Community Preventive Services. In addition, HHS collected comments from the public, federal agencies, and expert peer reviewers. HHS incorporated the feedback from these groups into the final draft, which went through formal departmental clearance to ensure that there is agreement and consistency across HHS.